In 2018, I moved away from my hometown for the first time. It came at a moment of great change in my life, but the main reason I left was to experience what it is like to live in English Canada. I had grown up in Montreal, the child of British immigrants, and attended a French immersion program from middle school through high school. In my 20s, I started to work in teaching and gradually built up my professional language skills. In my 30s, I was able to communicate in French at a high level and ultimately develop a career in instructional design that bridged the language gap. A specialty in translation and second language editing naturally emerged from this, as I was the last pair of eyes on every project I published. Nevertheless, when career advancement was on the horizon in middle age, I still struggled to get a foot in the door. To be blunt, it is not easy to be an English person in Québec.

Canada is made up of 10 provinces and three territories. Canadian national identity, such that it is, depends on the plurality of identities of which it is comprised—the diversity that has resulted from the mixing of different settlement and migration patterns with distinct geography, industry, and politics. Powers are shared between the federal government and the provinces, and indeed, it is hard to imagine how it could be otherwise, given the considerable differences between regions: the interests of the eastern coastal provinces, for example, have little in common with those of the prairies. Nevertheless, “English Canada” has tended toward a self-concept of hegemony by default, although it has no unified state or set of representative political institutions that adequately regroup all of the other identities that make up Canada. According to Angus (2003), “the name does not refer to the origins of its citizens considered individually, but to the language of everyday action and the institutional consequences of this dominance” (p. 25).

I grew up with this vague yet omni-present spectre of a great monolithic English Canada looming in the mega farms and industrial smokestacks of Ontario next door and the heckling of the City of Toronto, our overbearing younger sibling. However, as I matured, travelled more, and met new people, the sparkling diverse reality of the country began to break through.

In the 2006* Census, Canadians were asked to list their ethnic and cultural origins. A majority (59%) of Québec respondents self-identified as Canadian, while 29% self-identified as French. In New Brunswick, 50% of the population identified as Canadian and 27% as French. In Alberta and Manitoba, one quarter of the population identified their origins as English before Canadian. In Saskatchewan, British Columbia, and Yukon, at least half the population identified their ethnic origins to be other than Canadian. In the Northwest Territories and Nunavut, North American Indian and Inuit were the leading categories.

The identity of Canada as a whole is thus obscured; it cannot be said to either include or exclude “others,” such as the Québecois or First Nations. Yet this type of assertion is made all the time. Angus (2003) described such a dynamic as “constitutive paradox”—the absence of a hierarchical relationship between identities such that each can become the context or container for the other (p. 1). This resonates, as it comes close to describing my subjective reality of living as a minority within another within a nation within another that I, myself, cannot define.

In 1613, an early treaty between the Haudenosaunee and Dutch made use of a wampum shell belt to symbolize agreement between the two cultures. The design of the Two Row Wampum consists of two separate lines of purple wampum shells, symbolizing different vessels (canoe and ship) travelling down the same river, with three lines of white beads between them, representing peace, friendship, and respect. Borrows (2011) explained, “as nations move together side-by-side on the River of Life, they are to avoid overlapping or interfering with one another” (p. 76).

Evidently, this metaphorical worldview did not survive the colonization and “civilization” of the continent. Almost immediately, the new world was besieged by European problems – longstanding conflicts that simply moved to a bigger battlefield as soon as leaders recognized the economic value of the place. Yet, for a brief moment, there was what historian Richard White (1991) referred to as “middle ground,” a kind of quasi-neutral territory where each culture did overlap, learning from and contributing to the other’s experience (p. 50). The ability to communicate, either by studying the other’s language or by employing translators and interpreters, would have been key to negotiating middle ground.

In describing one of the least eloquent moments in Canadian broadcasting history, Conway (2008) addressed the attempts of anglophone and francophone journalists to explain the complex 1987 Meech Lake and 1992 Charlottetown accords. These proposed agreements were intended to garner Québec’s support for the Constitution and certain of its amendments (and stave off the province’s drive toward separation from the rest of the country), but the effort ultimately led to confrontation, with Native groups, in particular. The Canadian Journal of Communication (2008), in its abstract of Conway’s work, described the problem this way: “Two forms of translation played central roles in their coverage: linguistic translation, when journalists speaking one language quoted a politician speaking another, and cultural translation, when journalists interpreted Canada’s diverse communities for viewers.” Unfortunately, translation strategies failed on several occasions, resulting in the misrepresentation of some important terms and concepts, which may have contributed more to the debate than the facts themselves.

The contribution of language to the establishment of neutral territory between co-existing yet essentially separate worlds is capricious. When the precise sense of a term or the spirit of an expression cannot be translated, interpreters may unintentionally overlay their own perspectives, producing at best an approximation of the original meaning, at worst a complete falsehood. This is true of vocabulary but also, and more importantly, of context. The role that language plays, the form it takes, and the skill with which it is deployed are essential elements of cultural development. We know this intuitively, but the connection between language, culture, and thought is unclear. The concept of middle ground, then, is compelling when considering any definition of Canada, either past or present.

Peace, freedom, security, and diversity are just a few of the qualities Canadians will readily admit they value, but if queried on how these ideals came to be, their answers will be as varied as the content of history textbooks in different parts of the country. The juxtaposition of cultures and ensuing rhetoric of opposition and conflict have been characteristic of the political discourse from the outset. The nation is, after all, as much the product of war as it is of migration – war between European conquerors, war with the Indigenous peoples, war against nature. These wars, which emerged primarily from economic and territorial claims, also included important philosophical and moral elements. “Like the natural world,” wrote Strand (2008), “[Native people] were domesticated, contained, controlled and dominated, even as their former ‘wildness’ was romanticized in myth” (p. 40). Furthermore, although France formally ceded Canada to Britain in 1763 at the close of the Seven Years War, both rivals continued to occupy the colony. The difficulty inherent in defining nationhood against such a backdrop of division is obvious.

The truth is, Canada is built on a foundation of mutually exclusive ideologies that manage, despite their incompatibilities, to co-exist. Whether they thrive or not is another issue and one of the most important challenges of the next generation.

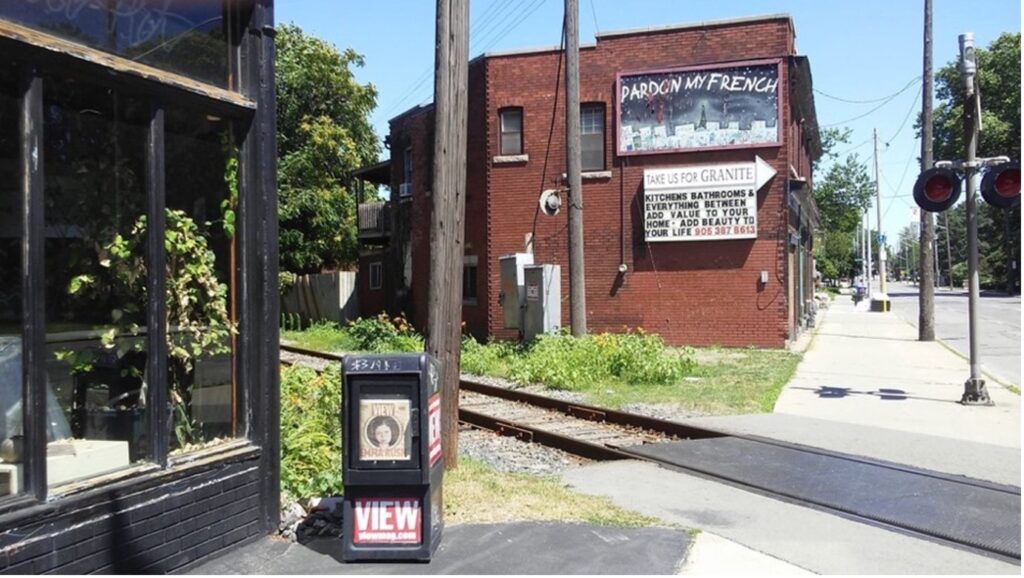

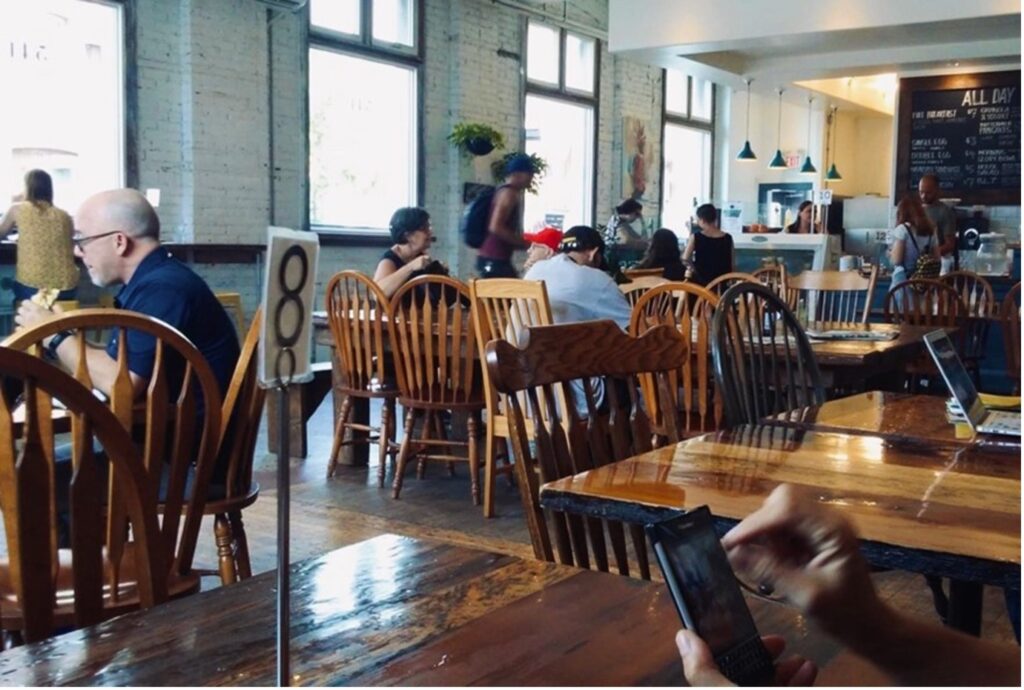

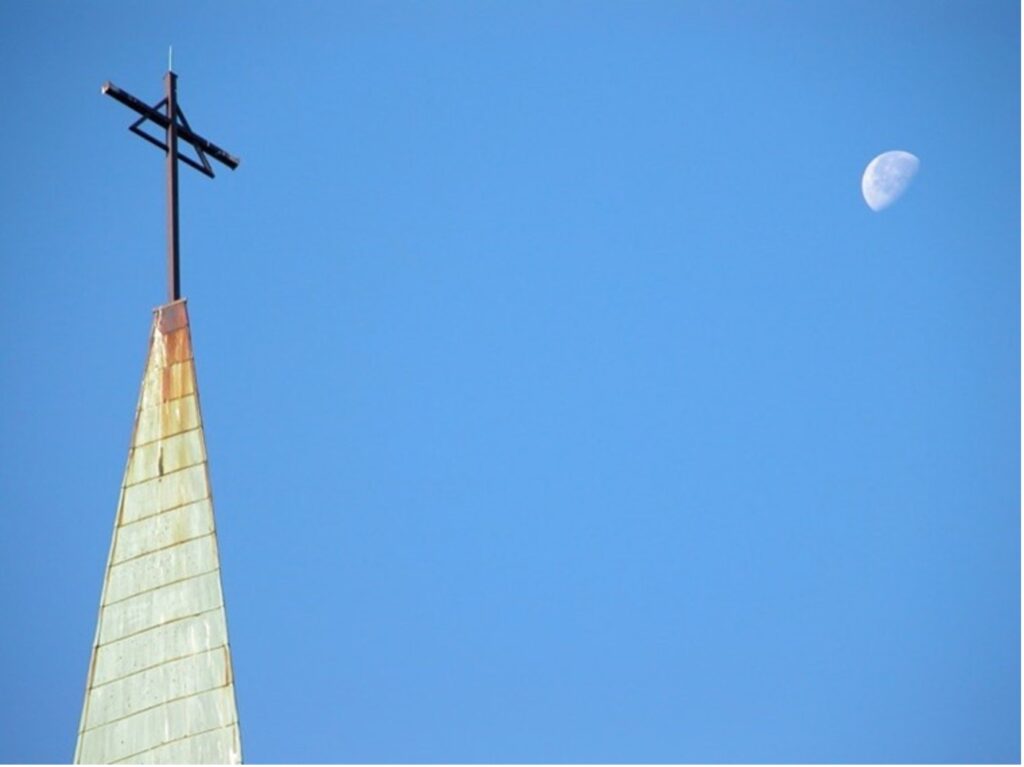

I had about 18 months under my belt in English Canada when the pandemic hit. Buoyed by my freelance work with CACTUS and others, I had been working hard while having the freedom to travel to visit my family. I had made friends and was starting to get to know this old industrial town, which was just beginning to re-invent itself as a bit of a destination for artists, architects, and educators. The light here is the kind that painters love… like in the south of France or the Cape Cod Bay (perhaps you know of a similar place in your own region). I also confirmed my suspicion: English Canada is different, but this little part of English Canada is also different from the one next to it, and so on.

It’s now been well over a year since I’ve seen any of the people who mean the most to me. There is so much literal ground between us, I wonder where the middle is. My focus has changed, as it has for most everyone. When I do step out into the world again, I think it will be with much more sensitivity to the edges – to those places where we conflict or imperceptibly touch. That is likely the real wisdom of the wampum belt: while it pretends to present an image of separation, it is not set on land but on the river that connects us and causes us to flow inexorably into and out of one another’s waters.

About the author

Valerie Paterson is a freelance editor with Cactus Communications.

Editor Talk is a new series where freelance and contractual editors share stories about their life and give you a glimpse into the freelance/contractual world. To explore freelance/contractual opportunities with CACTUS, visit here.